THE PUBLISHING HOUSE AS A MANUFACTURER

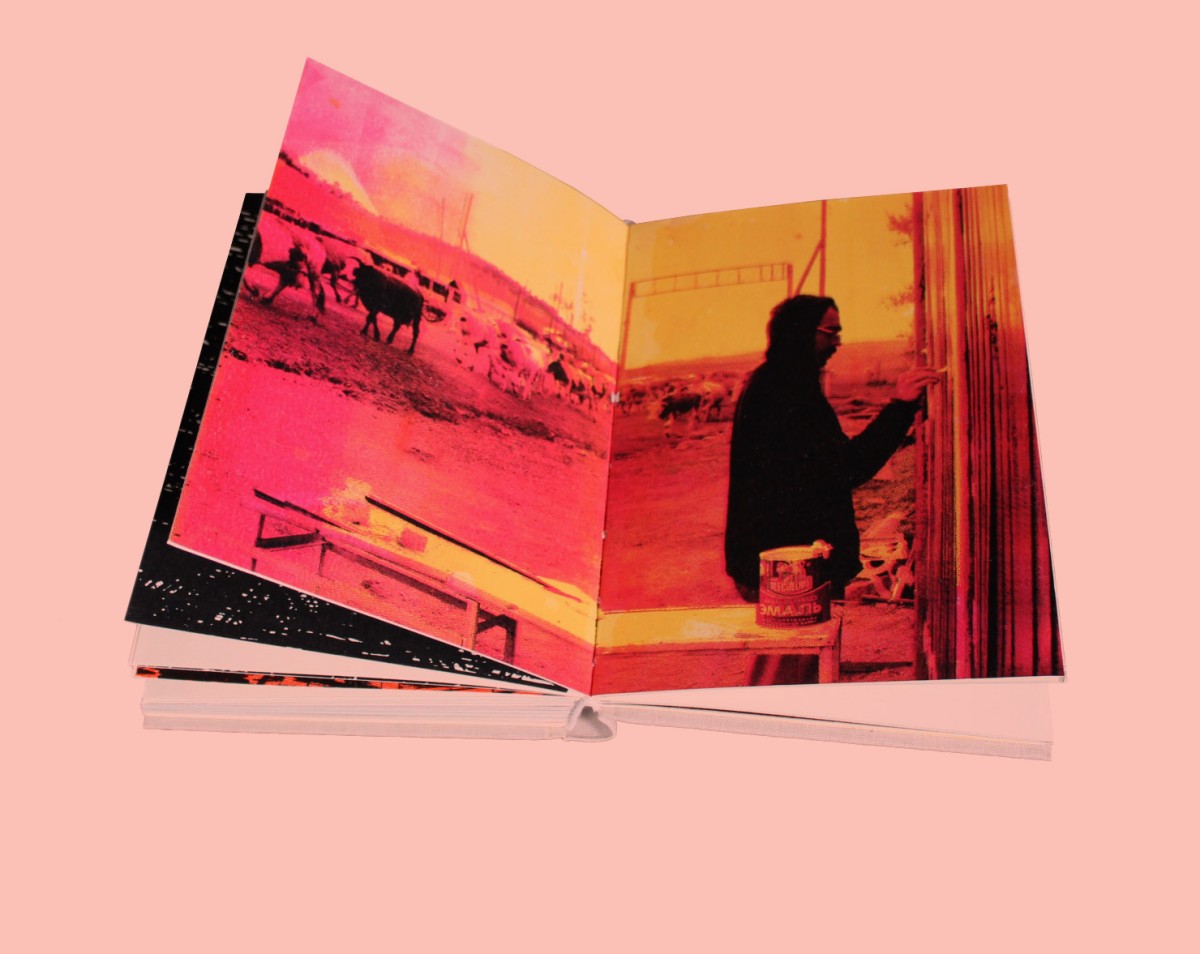

Polish studio and art book publisher Oficyna Peryferie is considered to be a creator of niche objects in their home country. However, owner Michał Chojecki is working hard to make sure that his organisation is seen as a business as much as a maker of artworks.

Where would you position Oficyna Peryferie in the larger field of art and design in Poland? And how would you describe your contribution?

In the Polish art scene, Oficyna as an organisation is one of a kind. Today there are several student groups making zines or prints and new printing workshops that are working with Riso or silkscreen. However this work consists of the creation of ephemeral objects and structures. My plan for Oficyna has been, from the very beginning, to create a long-term project.

As a practicing artist, I’ve always been interested in not only publishing, but most of all in making art. That’s why the idea of the publishing house as a manufacturer is so important for me. I try to be as professional as I can and as independent and free as possible. This type of printing is often thought of as niche in Poland – one of my goals is to change that perception.

In addition to publishing, you also work with Riso printing, silkscreen printing, and book binding. Does this mean you are self-sufficient when it comes to running the press and printing books? And how would you describe the economic model that the publishing house is run by (inside a capitalist system, a non-profit, a friendship economy, a non-capitalist economy)?

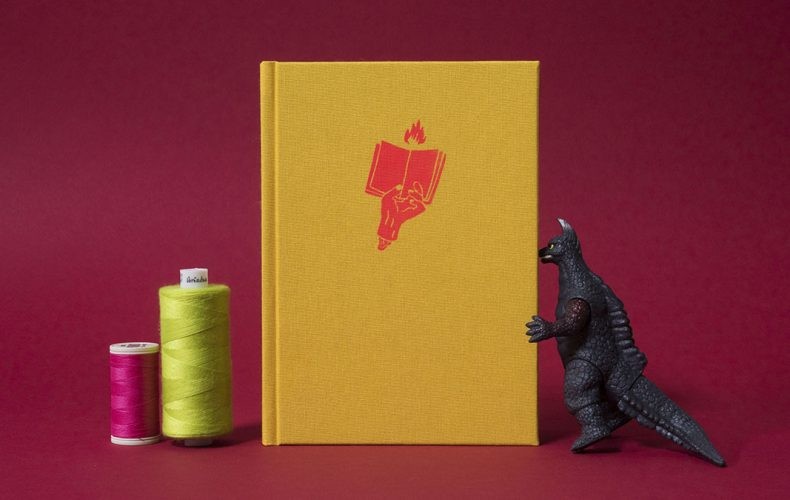

Our self-sufficiency has recently come to an end. I just sold our Brehmer 39 3/4 thread stitching machine, which we have used to make books. Preserving the machine was simply too expensive and complicated; since we didn’t produce thousands of books daily, it didn’t make sense to own it. We have decided to bind books externally and focus only on printing. That’s the end of the beautiful utopian dream of Oficyna.

I used to talk a lot about our economic model, because as probably everybody can guess, publishing art books and zines is unprofitable. Being a self-sufficient publisher is a very expensive hobby. There is also a very limited audience when it comes to art prints in Poland – there is no money, no public, and art prints are seen as a niche objects.

“Being a self-sufficient publisher is a very expensive hobby

Oficyna functions as a company: we sell prints and tickets for workshops, earn money, and pay taxes. Basically, we are happy capitalists. On the other hand, we have a social programme where if you don’t have money to attend a workshop, you don’t pay or pay a reduced fee. I don’t check if people lie or not; in general I believe in people. “Trust is the currency for the future” – I read it in a book about how to become a millionaire.

On your website, you write about how an interest in education has fuelled your practice as Oficyna Peryferie. Apart from the obvious concept of the book being used as a tool to mediate and spread knowledge, what is it about book making that lends itself so willingly to educational situations?

For the last four years, we have conducted more than 120 bookbinding workshops in the biggest big cities in Poland.

It’s surprising how popular the workshops are and this has changed my thinking about making books as something exclusive and not for everyone. Everyone can make a book, even complicated ones.

Every day we use books; we collect them and they have a special place in our culture. When I was a child, during the communist regime in 1980s Poland, my parents risked their freedom and lives printing underground independent publications. That’s a great testimony to how important books can be and that manufacturing them is also possible outside of “the system”.

Lastly, in the field of arts and design publishing, the 2000s and early 2010s were dominated by discussions around self-publishing. What do you believe is the most pressing and contemporary discourse in the field of arts publishing today?

I think for last 20 years there has been a general excitement concerning the Internet and its inherent publishing possibilities. For example, the last two decades have changed zine culture radically. Making printed matter today is not only reliant on wanting to communicate because there are easier and cheaper options available than printing a zine. Simultaneously, most technical barriers of publishing have disappeared with the arrival of easily accessible software, free online tutorials, and cheap printing. Today it’s very easy to create publications.

From my perspective, the biggest challenge is how we distribute what we produce. I know many publishers who produce books with no idea of what to do with them afterwards. How can we put in place the sustainable distribution of art books and prints? That is the most important issue that needs to be discussed.

©BABF2018